I’m not perfect, but I’m perfect for you

The artistic collaboration of Roxy Topia and Paddy Gould.By Linda Pittwood, 2018

Ceramics appear to be dipped in rainbows or glazed with nail varnish. Some are finished with a smooth disruptive puff of bespoke textile. A proud but jovial horse-like object elegantly wears a clitoris for a face. Snakes, bowels, anemones, curls of black hair follow the contours of ovaries. Artists Roxy Topia and Paddy Gould have been engaged in a prolific collaboration since around 2008. The multi-media practice they have developed together could be described as ‘maximalism,’ but in an odd way that word seems reductive. Their work is underpinned by drawings; both in the sense that they produce hand-drawn works on paper, but also that their sculptures, animations or even performance combine attention to surface design, with concept, form, texture and humour.

The 2012 exhibition Drip into Something More Comfortable established their interest in human idiosyncrasies and interactions, and the material culture of sex, using layers of imagery, sound, clashes of ideas and patterns. Perhaps not recognised legally, around this time they entered into an ‘artists-marriage,’ with vows that were written for the couple by an artist friend of theirs, Oliver Braid. “… I will photograph, photoshop and photomontage at your request…,” they read in a video animation titled I’m not perfect, but I’m perfect for you that used the vows as dialogue, “…Install with you, share observations with you…”.

They continued their inquiry into sexuality and their own romantic relationship in the works they displayed the following year in the exhibition Hubba Hubba. Specifically the narrative of the show was about “the maintaining of desire in a long-term relationship.” Bodies appear to have been deconstructed, then glued together with new types of tissue, cells or foreign objects. Their drawings shimmer like something alive and multiplying under a microscope, like an animation about to animate. Somehow their attack on the human body never seems macabre.

In their next show, Where the Magic Happens in 2013, body parts continued to be a central motif. Sometimes we can see recognisable human features, a nose for example, with additional noses hanging against a golden halo of iridescent afro hair. This show also introduced their interest in the bizarre language and anecdotes of Hollywood: the movies, press junkets and celebrity antics. They wrote in their press release, “The muscle memory in Jack Nicholson’s eyebrows has kept his skin limber year after year, re-enforcing his persona and our desire.”

Topia and Gould have occasionally curated and produced performance outputs, although they never let go of their own distinctive aesthetic. In 2015, they built a gallery and ‘Tiki bar’ in their back garden to exhibit the work of other artists and serve cocktails. The project was titled Duvet Days. It was intended to gently protest something un-specified, perhaps a reference to John and Yoko’s Bed in for Peace, 1969.

Treating their back catalogue like the ‘ink blot’ tests invented by invented by psychologist Hermann Rorschach, I tell Topia and Gould that I can see psychedelic record sleeves, microbes, brain cells, packaging and 1990s graphic design in their work. When I ask if any of these are deliberate references, they reply: no, not really, only the cells. Their work looks effortless, whilst much of the labour of meaning-making happens in the imagination of the viewer. Obsessions come in and out of focus.

Yet, their concern with sexuality and bodies persists. In The Internal Clitoris drawings, the shape of interior female anatomy is explored and interrupted. Sometimes the shapes of ovaries and wombs are formed with cherry cakes and a coiled spring. Another time by a coil of hair, the lacy frill of pair of underpants and a sea of microbes. Whilst the female form has been the subject of Western art for centuries, in their output it feels less pornographic than normal. Their sculpture One Size Does Not Fit All. Internal Clitoris, 2014 (the horse-like object) was selected for a group exhibition titled Sex Shop as part of the Folkestone Triennial Fringe. It was later featured on the British public-service television channel, Channel 4, in a programme called Sex in Class in 2015. The programme discussed new approaches to sex education in British state schools.

Topia and Gould’s exhibition Massages From the Second Brain, was held at Studio 1.1, London, UK and Monte Vista Projects, Los Angeles, USA in 2014. Drawings hang unframed on the wall, charged with energy and swirls of toothpaste. Ceramic objects hover at the cusp of disgusting. Over time their work becomes more Science-Fiction as the bodily forms from their drawings escape the page and become free-standing sculptures. By the time they produced the exhibition Great Pretenders, in 2016, aliens made simply of organs covered in the artists’ distinctive surface design seem about to walk out of the gallery.

An important part of the artists’ recent history is their 2016 year-long residency in Roswell, New Mexico, USA. Roswell is a real place but also a mythical one. In 1947 a flying disc was seen in the sky, which remains the subject of fierce debate. Was it a UFO? Or a nuclear test surveillance balloon? Topia and Gould’s work fits well in a place that can been seen differently according to what the viewer wants to see (and a place associated with extra-terrestrial life). Spending so much time in a remote location has clearly impacted them personally and artistically, and made them unafraid of diverting from well-trodden paths.

Their work has always been underpinned by their personal narrative and at a certain point they start to use the device of transcribing a conversation between them in their press releases. This is compelling, as in their work it is impossible to see where the contribution of one artist ends and another begins. (The interview for this feature could have been written by one or the other, or both). It helps them to reflect on their life and work, turning everything into a dialogue. After returning from Roswell they wrote:

Paddy: Picture this, for a year you are standing under the whole blue cloudless sky, expansive flat plains surround you and the brightest sun you have ever seen is beaming down upon you. The nearest big city is 3 hours away and to get anywhere you have to drive, you may or may not see anyone for over a week. Roxy: Sounds pretty great, well it was.

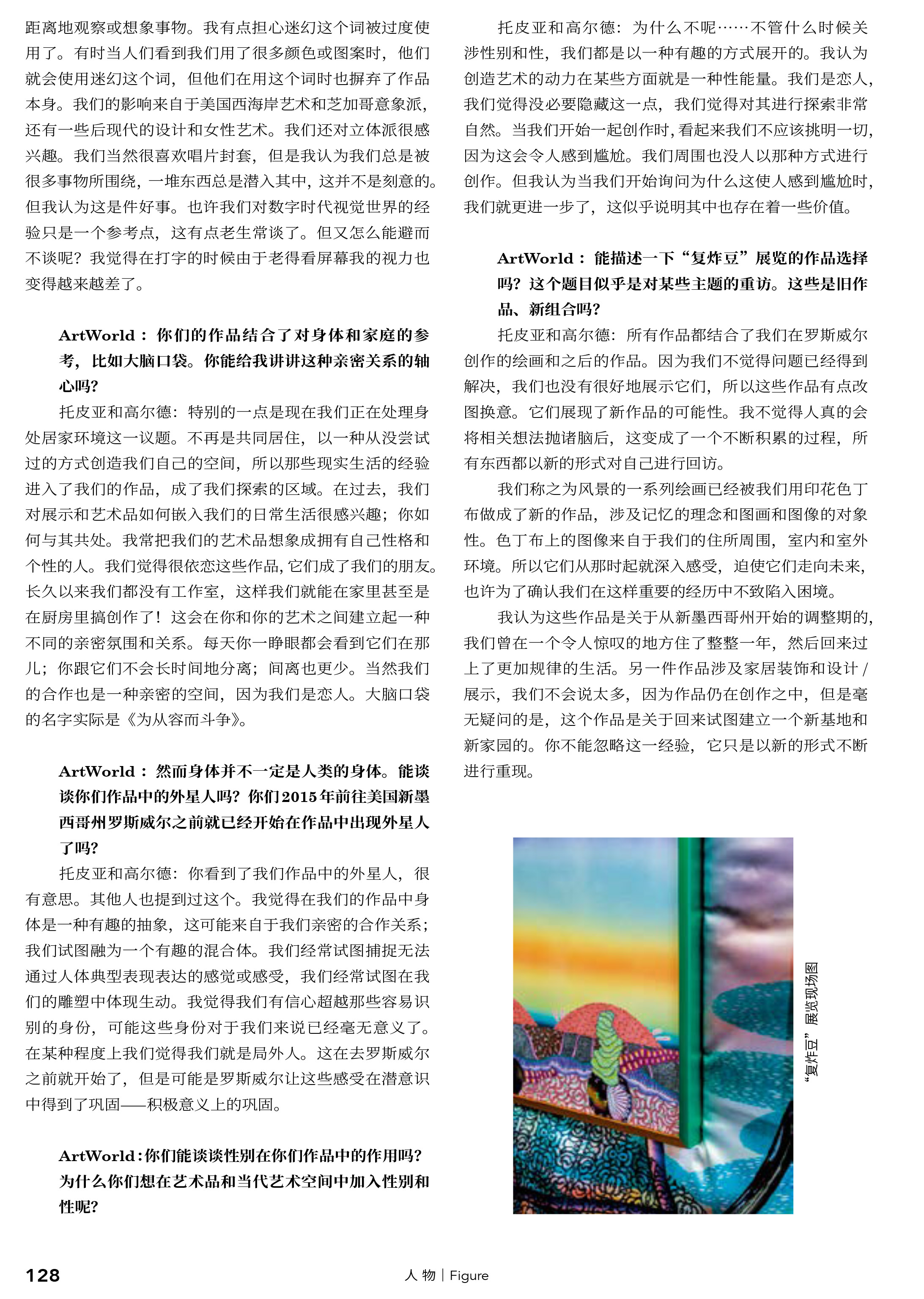

Bringing their story up to date, the artists recently held the show Refried Beans in Todmorden, a small creative town surrounded by mountains in rural England. The gallery is owned by artist Matthew Houlding, who disrupts the architecture of the white cube with sub-sections, open brick-work, different floor levels and coloured glass. The exhibition itself was an opportunity for Topia and Gould to reflect on their return to the UK (‘re-frying beans’ they intend as a metaphor for self-reflexion and re-creation) and the concurrent developments in their lives and their practice. They are now located in Birkenhead, Merseyside, a place not known as a cultural centre, but a location that allows them to access their networks in the vibrant city of Liverpool whilst working intensely in their studio across the river.

On another day with a cloudless sky, I ascend the stone steps to Matthew Houlding’s gallery. The artists have been experimenting recently with software that translates drawings into smooth, mechanical cuts in large sheets of fibreboard. These are displayed on a wall partially painted in purple, with textile and other objects hanging and peeping through holes. The push and pull of 2 and 3 dimensions. The pieces are large and heavy, but they have the quality of preliminary sketches.

Matthew Houlding’s own work is a presence within the show. As well as building the distinctive space for displaying other artists’ work, he has a studio beyond and a kitchen and storage area filled with large cans of paint and brushes. The result is convivial. Linking the kitchen to the main exhibition, Topia and Gould have lined up cans of baked beans, replacing the labels with the exhibition branding. Baked beans, a cheap, quirky but unexciting British food product are literally re-packaged here as Fine Art. Demonstrating the artists’ skill in making connections between disparate things and making these connections seem logical and coherent.

The centrepiece of the show is a beanbag, abstract but clearly meant to resemble a human brain. The beanbag is titled, The Struggle to take it easy. This is curiously appropriate amidst so much colour and movement in their signature heavily-worked drawings. The room is warm, but the coolness of the summer light and the different lines of sight in the space give the pieces room to breathe. At least for today, it doesn’t seem too difficult to take it easy. There are some feet in their new works, perhaps hinting at the many points on the global map that trace their recent trajectory. Or perhaps the feet are just resting before the two artists change location again.